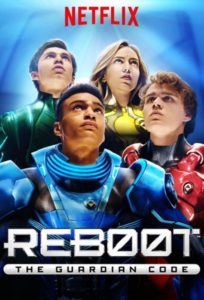

We were lucky to have Showrunner Larry Raskin join us for a lunchtime Q&A this week! Larry’s credits include Executive Producer of Reboot: The Guardian Code, Series Producer for Yukon Gold, and Director/Story Editor for Ice Pilots NWT.

On ReBoot, you hired writers who didn’t necessarily have experience writing for animation or for kids. What were you looking for?

On that show, I had a nice balance of serialized drama writers and comedy writers, including in the kids’ space. I hadn’t worked with any of the writers before, but it worked out. The main criteria for me is always a sensibility match. Being in a room is intense and very constant. You need to be able to share a sensibility for shows with a specific theme and approach. It accelerates the process. I’m also open to a voice that, if not a sensibility match, is complimentary.

How did you get into writing for TV?

I never thought of doing anything else, which is foolish! I did an undergrad in communications at Concordia and took a lot of writing courses as electives. Then I started working in the industry in Montreal, getting entry-level jobs. I got work on a six-show co-production with an Ontario company and a Quebec company. I went from being the producer’s assistant, to being the story editor on set. It was a fully immersive experience, working with the writers, the cast, and with the directors. After that, my wife and I moved to Toronto. I got a job with Atlantis Films doing development and story editing. That’s when I got the opportunity to start producing series.

When I moved to BC, there were fewer opportunities for scripted television, so I moved into factual television. I did ten years of cool factual shows and then finally got back into scripted with Reboot: Guardian Code.

How is story shaped in factual TV, as opposed to scripted TV?

Factual TV uses similar storytelling skills but you’re working with what you have, as opposed to what you want. The story process works backwards. You aren’t preconceiving the story lines.

In the shows I did, we followed professionals doing their jobs. Ice pilots was set in Yellowknife, and Yukon Gold followed miners in the Yukon. Real people were doing real things. The way those shows are shaped is through discussion with the main subjects, (what are their goals, what is likely to happen,) and then being extremely nimble and responsive to what does happen. A story takes shape in the moment, often through circumstance that was not foreseen. Your crew and your story team are always trying to figure out the potential of a story, and what elements are needed to make it a great story. It happens in the moment, and then it happens again once you recover that footage, review, analyze, ask for pick-ups, and start to shape it in the story editing and writing phase. Often you use interviews to fill in gaps that you don’t have footage for, but also to provide an insight that makes it more personal. If you ever get the chance to work as a story editor in factual, it’s an amazing opportunity to hone your story muscles and your editing skills.

Do you have any advice when it comes to working with agents?

Look for an agent who gets you, and who you think would give you the extra leg up that you need. What they’re looking for is something that makes you different from everyone else on their roster. When you’re talking with agents, you need to know your brand.

Do you have any advice for writers new to being in a room?

Not contributing is dangerous because it raises the stakes to be brilliant when you finally do speak. That said, you don’t want to dominate. Like in acting, listening in a writers’ room is crucial. Like musicians, you need to understand what track is being played, and not throw in ideas for another track at that time. It’s like jazz riffing. All the instruments need to play together and support each other. Tune in to what is going on. What you bring, in terms of positive energy, will almost always be returned to you.

Do you have any advice for newer writers handing in drafts to their showrunner?

On your own projects, you have the luxury of continually changing your script until you feel it’s the best it can be. Writing for someone else’s show is really about servicing their needs and the show’s needs. It’s a different skillset. If the outline is strong, focus on delivering in terms of structure. That way, if you even get halfway there in terms of character and dialogue, you’re giving the story department something very useful to work with. If you deviate from the outline and come in with a bunch of new ideas, it could be brilliant but often there’s no time for that. Check in with your showrunner about your ideas, but I would say no showrunner wants big surprises when you hand in your draft.