Blog

Blog

Play: How to Write An Original Spec Script Part 1

Photo by Park Troopers on Unsplash

The PSP is accepting applications for our next scripted series lab until September 1st, 2019. Six writers will be given the opportunity to create a new tv series with an experienced showrunner. Interested? We want to read your original tv script! If you’re wondering how to write an original spec script, the first step is coming up with an idea. The whole prospect can be a bit daunting when the options are endless. Sometimes it helps to remember that this is something you’ve been doing since you were little.

Play Like A Little Kid

Okay, let’s imagine you are a five-year-old kid looking into a box of toys in the corner of a waiting room. You’re digging around to see what you want to play with. Then you find three green plastic army guys, a red plastic bendy monkey, and a small wooden horse with one leg broken off. So those are your characters.

Next, you look around to find a spot to set them up. Under your mom’s chair will do nicely. You’ll have some privacy and, even better, you can use her big brown leather purse as a mountain for your characters. This will be your world.

It turns out that Purse Mountain is full of treasure. The army guys have it and are guarding from above. Bendy Monkey promises Horse that she will find a way into the treasure cave in Purse Mountain to get the elixir that can restore Horse’s missing leg. Horse is grateful but very weak. Bendy Monkey is scared but determined. You realize that Horse is suffering from a curse made by an evil wizard back when he rescued Bendy Monkey from a cage in the wizard’s library. If Bendy Monkey can’t get the elixir quickly, then Horse’s other legs are going to break off. That’s your conflict and those are the stakes. You could say that it’s really a story about friendship solidifying courage in. That’s your theme.

Test Your Idea Like A Kid Looking For Someone To Play With

You are going to feel an urge to just start, but hold on! You need to test the idea on other people first, so experiment until you have a logline you can actually say smoothly out loud to real people. (I mean it! REAL people! Not just to yourself out loud. Be brave.) But back to Purse Mountain, as a kid, you would have said, “Want to play? Bendy Monkey has to get past the guards to save Horse.” That’s your log line and your pitch.

In other words, narrow it down to writing the kind of show you yourself would want to watch. Imagine your world and get as specific as you can. Then figure out the conflict. What mess will the characters get themselves into? Is this mess powerful enough to be your story engine through multiple episodes? What personalities and character attributes would create the best web of complications and conflicting views? Doodle, brainstorm, make an imageboard or tape up creepy webs of photos connected by yarn. Do whatever helps you to really understand what adventure you want to play.

That’s where you always start. Don’t worry, you’ve been doing it since you were small!

The Confusing Curse of TV Script Formatting: Guest Post By Kat Montagu

Photo by Bruno Martins on Unsplash

In television, every genre and every series has a different formatting style. So, when you’re writing an original TV pilot script, how do you know which rules apply? There are some guidelines that apply to all TV scripts.

If you don’t have screenwriting software yet: Set margins 1.5 inches (3.8 cm) from the left page edge. Write the character names in caps 3.5 inches (9 cm) from the left margin. Set dialogue 2.5 inches (6.3 cm) on each side from the margins. But you’ll need screenwriting software eventually. TV writers in LA tend to use Final Draft. TV writers in Vancouver tend to use Movie Magic Screenwriter.

Next, write your act breaks into the script (centred, capped and underlined). Remember to write END OF ACT ONE before you write ACT TWO. Streaming video on demand (SVOD) shows (like Netflix’s Stranger Things) and some cable shows don’t need written act breaks, but they still have inherent act turning points and you’ll need END EPISODE (capped, underlined and centred) at the end.

Where should you place your ACT BREAKS?

Pick a show in your genre and analyze its specific formatting and structure. Here are some typical examples of act break structure.

HALF-HOUR COMEDY

TEASER or COLD OPEN – 2-4 pages

ACT ONE – 6-11 pages

ACT TWO – 6-11 pages

ACT THREE – 6-11 pages

TAG or STING or ACT FOUR – 1-4 pages

Total 21-41 pages (Multi-camera sitcom scripts tend to be longer. Single-camera half-hour comedy scripts tend to be shorter.)

ONE HOUR

TEASER or COLD OPEN – 2-4 pages

ACT ONE – 11-13 pages

ACT TWO – 11-13 pages

ACT THREE – 11-13 pages

ACT FOUR – 11-13 pages

ACT FIVE – 11-13 pages

TAG or STING – 1-2 pages

Total 58-65 pages

Formatting the TITLE PAGE, CAST LIST, and SET LIST:

Now set up your title page. TV writers use Courier 12 for the script, but sometimes Times New Roman for elements of the title page.

Most TV series have logo titles.

For the pilot script:

SERIES NAME

“Pilot”

Written by

Jane Doe

On the bottom left of the title page, list contact information. The bottom right in bold is revision information:

WHITE PAGES month/day/year

Some TV scripts also have a REVISION HISTORYon the next page to keep track of changes (White, Blue, Pink, Yellow, Green, Goldenrod, Buff, etc.).

Eg. DATE COLOR PAGES PUBLISHED

08/29/19 (FULL PINK) FULL SCRIPT

Next page: CAST LIST. Roles on the left, actors on the right. ALL CAPS.

Next page: SET LIST. Interiors on the left. Exteriors on the right. Establish the house, then indent rooms below it. All caps.

INTERIORS

VENICE BEACH BUNGALOW

LIVING ROOM

KITCHEN

EXTERIORS

KAT’S HOUSE

BACKYARD

FRONT YARD

Multi-camera sitcoms (like Big Bang Theory) film on standing sets, using stock footage for exteriors, limiting locations and characters. Single-camera comedies (like Brooklyn 99) shoot exteriors too. A typical one-hour drama might have 60% interior sets and 40% exteriors. I mention this because TV writers are also producers (partly responsible for budgets).

After writing the set list, close the title page and save your document.

Create a Header to start on p2.

These vary, but usually contain some, if not all, of this information:

SERIES “Episode” #101 10/03/19 (COLOR) Page number

Now, finally, you’re ready to start your script.

FADE IN:

This is where half-hour and one-hour formatting diverge…

ONE-HOUR DRAMA

Unless the scene ends exactly at the bottom of the page, use CONTINUED: top left and (CONTINUED) bottom right. The second continued page says CONTINUED: (2).

Add scene numbers on either side of bolded scene headings.

Establish DAY or NIGHT in scene headings, then use CONTINUOUS or LATER. Many writers add (D1) or (N2) to mean Day One or Night Two in the fictional timeline.

No more than four lines of action-description. Use italics, underlining, caps and bolding for emphasis. (Check out the Lost or Stranger Thingsscripts.) Fragment sentences with double-dashes for a new shot —

— even in the middle of a sentence.

TV writers refer to the camera (sometimes as “we”).

WE PAN across the room.

Capitalize PROPS.

Single-space dialogue, like a feature script.

Use parentheticals not just for tone and action but also to direct a line. “re” stands for “regarding.”

ROSETTA

(re: Hazel)

What’s wrong with you?

HALF-HOUR COMEDY

Use scene numbers on either side of CAPITALIZED AND UNDERLINED scene headings then write the characters appearing in those scenes below in brackets.

INT. DINING ROOM – NIGHT

(ROSETTA, HAZEL)

Once you establish DAY or NIGHT, use CONTINUOUS or LATER instead.

The first time a character appears, cap and underline their name with a brief description.

Intense HAZEL (24) and hipster ROSETTA (22) drink wine.

Only NEW characters get caps in subsequent episodes.

Some comedy series – like Friends, Two and a Half Men and Big Bang Theory– CAPITALIZE action-description and double-space dialogue, but others – like The Good Place and 30 Rock– lower-case action description and single-space dialogue. Double-spacing dialogue changes the 1:1 ratio, so a 22-minute episode may be 44 pages long. Confusing? Sure. Just make your decision and stick to it.

Underline and bold dialogue for emphasis.

(CAPITALIZE PARENTHETICALS IN BRACKETS) on the same line as dialogue with no indent.

HAZEL

(TO ROSETTA) What?

The best way to get good at formatting TV scripts is to read a lot of TV scripts. My favourite source is Lee Thomson’s amazing TV Writing collection https://sites.google.com/site/tvwriting/. Check out his TV Bible collection too.

Kat Montagu is an award-winning screenwriting instructor at Vancouver Film School and the author of The Dreaded Curse of Screenplay Formatting (available as a bestselling eBook on Amazon).

Scripted Series 2020 Info Night

Thank you to everyone who attended last night’s Scripted Series Lab 2020 info session! We are excited to see so much interest. We’d like to send a special shout out to last year’s participants who generously answered questions and entertained us with their anecdotes.

We hope you will email us with your questions if you weren’t able to attend last night’s event! Also, be sure to sign up to our mailing list if you haven’t already. We plan to hold an online info session later in the summer. (Details still to come.) The application window for our 15 week 2020 Scripted Series Lab closes September 1, 2019. Please have a look through our SSL FAQ and send in your original TV pilot scripts!

7 Gems from the Toronto Screenwriting Conference

Photo by Andrew Bui on Unsplash

The TSC Fellowship recipients are back after a whirlwind conference weekend in Toronto. Here are seven pieces of advice from conference speakers, on topics ranging from mental health to writing, pitching, and receiving notes.

On looking after your mental health:

“You don’t need to be sick or in pain to create something.”

-Christopher Cantwell. Showrunner, Halt and Catch Fire @ifyoucantwell

On creativity and discipline:

“The most important thing is to write every day. Your two most common enemies are procrastination and perfectionism, two sides of the same coin. Your mind tricks you into not doing the work. Push through and write the words regardless. Find a path to your subconscious. Some days are harder than others. Creativity is elusive – capture it by work ethic. Just keep working. Writing every day on a schedule is like training for a sport.”

-Carlton Cuse. Showrunner, Locke & Key, Lost, Bates Motel @CarltonCuse

On theme:

“Know what each character wants at the start of each season. That want needs to be in each episode with characters making both good and bad decisions based on that. It colours everything they do. Then you get ready to blend them together based on episode theme to get the stories to talk to each other. That makes it cohesive.”

– Ayanna Floyd Davis. Showrunner, the Chi @qu33nofdrama

On writing your pilot:

“Anyone who is reading your pilot has probably read a thousand pilots, minimum…meaning you probably can’t surprise them. But they still want to be surprised. Subvert their expectations and focus on twists of character rather than plot. Let the characters feel familiar, then have them do surprising things.”

-Ben Watkins. Showrunner, Hand of God @_Benipedia_

On cutting through the marketplace noise:

Always be saying something. Be innovative and provocative. You have to be able to cut through in this market. People are hungry to see things subverted and see themselves reflected.

– Heather Brewster. VP, Scripted, Global Content Div, Keshet Int’l @HtoTheBrewster

On pitching:

“If you’re pitching as a team, practice as a team. MULTIPLE TIMES. Assign specific roles. “Before I let Kevin answer that, I’ll give you some context…” Prepare your answers to all anticipated talking points.

– Kevin White. Speaker and Pitching Coach @TheOptimalPitch

On receiving studio notes:

Listen to what is being said and try not to interrupt even if you disagree. Ask them specifically, “what’s driving the note?” Then you can figure out if it’s a matter of opinion vs truly constructive. It’s okay to say “let me think about that.” Be willing to at least consider or even try what’s being suggested. Fight for what you truly believe in. Let go of things that don’t affect the integrity of your project.

-Phil Breman, VP Scripted Programming, NBC @PhillingYourDay

We’d like to thank the organizers of the Toronto Screenwriting Conference for their dedication to bringing in such wonderful speakers. We’re already looking forward to next year!

Were you there too? What speakers stood out for you? Are you planning to go next year? We’d love to hear about it.

You can’t make these people up! Karen Lam On Doing Your Research

Photo by Matthew Ansley

Karen Lam, (Ghost Wars, Van Helsing, Evangeline), offers some fresh advice on the importance of doing real world research.

Do you think TV writers need to do research outside the writers’ room? If so, what type of research?

You can google stuff about serial killers, but I’ve spent months actually talking to FBI agents and inmates, doing first hand research interviewing people. I can tell you it’s not the same as looking something up on Psychology Today. You can’t make these people up! Real cops sound different than they do on tv. Victims of horrible crimes aren’t just dark and mopey. They act differently than on tv.

To me the more first-hand non-tv experience you have, the better. It’s important to go out and deal with real humans.

What influence has your documentary work had on your writing for film and television?

My documentary work balances my fiction writing because these people’s stories change me. They change how I view the world. It’s important that I’m not going in with an agenda. I’m not trying to direct them into saying anything. When I’m doing my documentary research, I just stay in the moment and trust that if it’s going to be important to my other projects it will percolate and stay with me.

When you go out there you have to understand that people are complex, and you may not get the answers you were expecting. The questions that you ask should be open ended and you have to be there to listen to them. I give people space. It’s a conversation, not a set of questions, and I never know where the conversation will go.

As writers I think it’s really important that your reality gets reflected with specificity. It’s the details that make it real. When we’re not using our own backgrounds or our own real-world research, characters can just seem like copies of copies of characters.

Our whole job is to be a vessel, and to give some sort of voice to what needs to be spoken. I say have as little ego as you can so you can have compassion for your characters and be open to what comes. Go talk with real people. Do primary research. Get yourself into a situation where you get access to real stories and real situations. Otherwise what are you doing but regurgitating?

How Do I Turn My Love of Writing Into a Screenwriting Career?

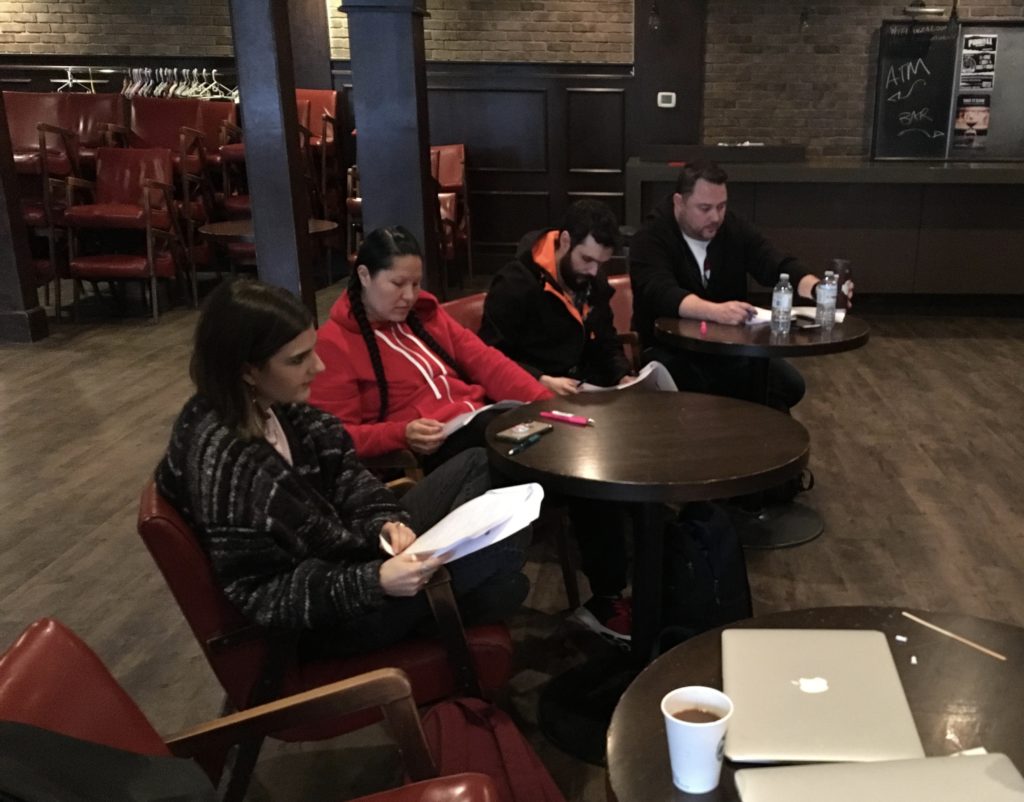

2019 Scripted Series Lab Table Read

We received a question this week from someone who loved to write but wasn’t sure how to turn their writing into a career. I thought I would share my thoughts on the blog in case there were others reading with the same question.

First let me say I wouldn’t have felt qualified to answer this query except that I’ve now had the pleasure of interviewing several television writers and showrunners with our scripted series lab. Although each writer seems to have found his or her own unique career track, one consistent thread between them is that they all managed to make circuitous but ultimately important connections in the film industry. They also share the traits of being humbly dedicated to working on their craft and working hard. I’m sure I won’t be the first to come up with this conclusion but I now believe aiming for a career in tv and film writing requires a two-front strategy:

- Make connections in the film industry…in every and any department.

- Be a professional – meaning always be writing and working on your craft.

Get in anywhere you can. Whether you are a PA on set, working in the accounting department of a production company, building sets in the carpentry department, or logging footage for documentaries, you never know how your connections and understanding of the wider industry will help you get a script to the right person who can help you get your next opportunity and so on. Be invaluable at your job, be someone people want to extend themselves for, and let people know that you are also a writer. Volunteering at film festivals can also be a useful way to meet people and learn more about how writers fit into the industry.

While you build your network, you have to continue to work on your craft. Pump out that material, draft after draft, and you’ll get better with each one. Try different genres. Write original material and non-original specs to show you can write in your own voice or adapt to someone else’s. Create an ironclad routine for your writing. There are many great books that a quick internet search will reveal.

There are some great teachers in our local screenwriting programs. Check out the full and part-time options at UBC, SFU, Capilano University and Langara. Also, check out Raindance, InFocus and Vancouver Film School. Here at the PSP we accept applications for our highly competitive scripted series lab, (running January-April) beginning in August.

When you feel your work is ready, you can start entering your scripts in screenwriting contests. Making it to the finalist round of any of the major competitions is a great way to get the attention of industry decision makers. Making your own short films or web series’ can also be a great way to showcase your work and your ability to make things happen.

Beyond craft, there are some great websites and podcasts to help you understand the business of screenwriting. Some of my favourites podcasts include: Script Notes by John August, Write On by Final Draft, On the Page with Pilar Alessandra, and Storywise with Jen Grisanti. Both the Writers Guild of Canada’s Writers Talking TV, and John Ward’s 49 Degrees North focus specifically on writing in Canada.

I would to hear from working writers out there. Do you have any tips for turning a love of writing into a screenwriting career?

Your Cops Have to Talk in the Car! Know Your Obligatory Scenes and Conventions

Photo by Matt Popovich on Unsplash

Given Showrunner Sarah Dodd’s CSA winning talent for binge worthy police drama, we are pretty excited to reveal that the scripted series lab is working on a new crime series. I asked our writers if they had any advice for nailing the obligatory scenes and conventions of this beloved genre and here are some of their notes:

You’ve got to have the bullpen recap to summarize what’s known so far in the investigative line and to clarify the direction of the investigation.

Your cops have to talk about the case while driving in the car!

The protagonists need to drive their scenes. They are acting out their own strategies, and we find deliciousness in the surprises that befall them.

Treat every suspect as a potential killer. Keep their motives and opportunities in mind.

You need to really humanize the victim.

Have a red herring switch that’s going to flip the investigation on its head.

As one of my favorite experts on story, Shawn Coyne, explains, “Conventions are elements in the story that must be there or the reader will be confused, unsettled, or bored out of their skull.” Coyne has three steps for finding your obligatory scenes and conventions in his “the Story Grid” podcast:

- Decide which kind of story you want to tell.

- Find other stories like the one you want to tell.

- List all the things they have in common.

We barely scratched the surface with our crime drama tropes, so what did we miss?

Damon Vignale on Showrunning and The Murders

Jessica Lucas as Kate Jameson in The Murders

Damon Vignale dropped in for lunch at the PSP last week. Damon is the creator and showrunner of the original crime-drama series, The Murders debuting on March 25, 2019. He was also a writer and consulting producer for The Bletchley Circle: San Francisco, and writer and co-executive producer for Ghost Wars.

How did you break in to writing for television?

It was kind of a happy accident. I started out writing and directing independent features. On my first film I worked with a producer, Ron Scott, who many years later asked me to give notes on a comedy series he was producing, Mixed Blessings. He liked my input and assigned me three scripts. Ron showed me a pilot he was also working on, called Blackstone, and I knew immediately it was something I wanted to be a part of. When the show was greenlit to series, he hired me as a writer-producer.

You’ve just finished working on The Murders. It was your first time as a Showrunner. Can you tell us about that transition?

It was a big transition. Being responsible for everything and everyone is very different from being there solely as a writer. Handling the writing and production, you learn quickly to delegate.

Because I came up making independent film, and I also worked for numerous years as an Assistant Director on commercials, I understand production. I think that really helped.

The writing room is where I always feel the pressure because it’s where the story starts. If the work isn’t good there, it’s hard to turn it into something great farther down the line.

How did you coach writers to get the work done when you couldn’t be there?

Having a clear vision of the show you’re making is important. I’m also open with broadcasters’ notes, so we’re all on the same page. I relied on my writer-Co-EP, Karen Hill to oversee the writing team when I couldn’t. We worked together on Motive and she’s an amazing writer. She had been involved since development and her input was invaluable. I felt confident in her ability to drive the scripts forward and stay true to the tone and sensibilities of what I wanted the show to be.

What did you look for when putting your room together for The Murders?

I wanted to put a room together that had different voices. I didn’t want to create a space where we just pat each other on the back. Of course everybody in the room needs to be respectful, and buy into what the show is. That said, I try to bring people in with different points of view, different backgrounds, and different interests. I think we managed to do that with The Murders. It meant that within our crime drama, we were able to go after some really interesting stories and tackle some contemporary issues.

It doesn’t matter what room you’re in; there’s always that feeling of, “Wait, how do we do this, again?” You start with a blank page and it’s daunting knowing you have to turn out a season of television. For me, everyone’s voice is equal and the best idea wins. Writers come in with good and not so good ideas, and they all count. It shakes things up and starts a conversation that often takes you somewhere you never thought you’d end up.

Do you have any advice for TV writers trying to break in?

If you don’t have experience, then your original spec material really matters. Also, if I get a recommendation from a more senior writer, that’s going to carry some weight. At some point you are going to need someone championing you. If you have an agent, that’s great, but I think developing relationships with other writers and producers is helpful too.

Send Your Darlings Out Into the Cold (Read)

Photo by Jason Blackeye on Unsplash

There is nothing as exciting, or as crushingly revealing, as handing over your script to a group of actors for a cold read. How thrilling! Your characters will come to life and you will cringe at some of the lines you thought you loved.

You may fight to urge to grab the script back when you realize how many extra words you’ve given your quirky love interest. You may…have…to…sit…and…suffer… while the actor heroically plows through what’s written on the page long after the scene has deflated around …your…your…typos and your very robustly magnificent usage of adverbs. (See what I did there?)

Perhaps you already read your work out loud when proofing in your pyjamas. Just don’t fool yourself into thinking that your solo read-aloud will catch as many issues as a read by people who aren’t familiar with the material. If, like me, you’re used to finding your typos immediately after hitting “send,” then you probably already mistrust yourself enough to recognize this wisdom.

Kim Garland wrote a great article explaining how to host a table read for Script Magazine. I would add that this exercise can be useful even in the very early “vomit draft” stages of a project. I’m lucky enough to have a screenwriting group that meets regularly to table read from our works in progress. The notes that I make on my script while listening to these reads are invaluable. I’m pretty sure it saves me future pain, and it’s also a lot of fun.

Q&A With Showrunner, Larry Raskin

We were lucky to have Showrunner Larry Raskin join us for a lunchtime Q&A this week! Larry’s credits include Executive Producer of Reboot: The Guardian Code, Series Producer for Yukon Gold, and Director/Story Editor for Ice Pilots NWT.

On ReBoot, you hired writers who didn’t necessarily have experience writing for animation or for kids. What were you looking for?

On that show, I had a nice balance of serialized drama writers and comedy writers, including in the kids’ space. I hadn’t worked with any of the writers before, but it worked out. The main criteria for me is always a sensibility match. Being in a room is intense and very constant. You need to be able to share a sensibility for shows with a specific theme and approach. It accelerates the process. I’m also open to a voice that, if not a sensibility match, is complimentary.

How did you get into writing for TV?

I never thought of doing anything else, which is foolish! I did an undergrad in communications at Concordia and took a lot of writing courses as electives. Then I started working in the industry in Montreal, getting entry-level jobs. I got work on a six-show co-production with an Ontario company and a Quebec company. I went from being the producer’s assistant, to being the story editor on set. It was a fully immersive experience, working with the writers, the cast, and with the directors. After that, my wife and I moved to Toronto. I got a job with Atlantis Films doing development and story editing. That’s when I got the opportunity to start producing series.

When I moved to BC, there were fewer opportunities for scripted television, so I moved into factual television. I did ten years of cool factual shows and then finally got back into scripted with Reboot: Guardian Code.

How is story shaped in factual TV, as opposed to scripted TV?

Factual TV uses similar storytelling skills but you’re working with what you have, as opposed to what you want. The story process works backwards. You aren’t preconceiving the story lines.

In the shows I did, we followed professionals doing their jobs. Ice pilots was set in Yellowknife, and Yukon Gold followed miners in the Yukon. Real people were doing real things. The way those shows are shaped is through discussion with the main subjects, (what are their goals, what is likely to happen,) and then being extremely nimble and responsive to what does happen. A story takes shape in the moment, often through circumstance that was not foreseen. Your crew and your story team are always trying to figure out the potential of a story, and what elements are needed to make it a great story. It happens in the moment, and then it happens again once you recover that footage, review, analyze, ask for pick-ups, and start to shape it in the story editing and writing phase. Often you use interviews to fill in gaps that you don’t have footage for, but also to provide an insight that makes it more personal. If you ever get the chance to work as a story editor in factual, it’s an amazing opportunity to hone your story muscles and your editing skills.

Do you have any advice when it comes to working with agents?

Look for an agent who gets you, and who you think would give you the extra leg up that you need. What they’re looking for is something that makes you different from everyone else on their roster. When you’re talking with agents, you need to know your brand.

Do you have any advice for writers new to being in a room?

Not contributing is dangerous because it raises the stakes to be brilliant when you finally do speak. That said, you don’t want to dominate. Like in acting, listening in a writers’ room is crucial. Like musicians, you need to understand what track is being played, and not throw in ideas for another track at that time. It’s like jazz riffing. All the instruments need to play together and support each other. Tune in to what is going on. What you bring, in terms of positive energy, will almost always be returned to you.

Do you have any advice for newer writers handing in drafts to their showrunner?

On your own projects, you have the luxury of continually changing your script until you feel it’s the best it can be. Writing for someone else’s show is really about servicing their needs and the show’s needs. It’s a different skillset. If the outline is strong, focus on delivering in terms of structure. That way, if you even get halfway there in terms of character and dialogue, you’re giving the story department something very useful to work with. If you deviate from the outline and come in with a bunch of new ideas, it could be brilliant but often there’s no time for that. Check in with your showrunner about your ideas, but I would say no showrunner wants big surprises when you hand in your draft.

The Horrible Woman Who Helped My Screenplay

Photo by Anders Nord on Unsplash

A stocky woman in her seventies, her hair as royally permed as the Queen’s, sits at a four-person table by herself. Her brown wool jacket has a seat of its own. Her cane is draped against the table leg at an angle in an effort to trip innocent passersby. I have already decided that she’s horrible. Is that nasty of me? More importantly, is my character description effective?

This woman, let’s call her DOREEN, has been shouting into her cell phone for forty minutes. We are all glaring at her. She hasn’t noticed. She’s too absorbed in her very important phone call with a friend. Let’s call the friend, FRAN. Doreen doesn’t think Fran needs to make too much food. No, Charles wasn’t there. Yes, she had a funny feeling about that, too.

A lipstick stained coffee lid, a bent paper cup, three crumpled napkins, and a ball of banana bread cling-wrap lie scattered across her table. On the remaining chairs, she claims territory with a lumpy plastic shopping bag, a dripping umbrella, and her oversized beige purse. I’ve seen mothers with toddler triplets dine more discreetly.

For those of us lucky enough to be sharing our precious time with Doreen, it’s quite clear that she’s a “space taker-upper,” and probably a taker in general.

I should thank coffee shop Doreen, whoever she really is, for giving me a real-life negative impression that I can put to effective use in my writing. There’s nothing like people watching when it comes to figuring out how to show rather than tell. As John August explains in his fantastic blog post, How To Introduce Character, “Look for details that have an iceberg quality: only a little bit sticks above the surface, but it represents a huge mass of character information.”

How have strangers in public spaces influenced your scripts? I’d love to hear about it.

Q&A With Writer and Producer, Matt Venables

Vancouver Based Writing Team, Matt Venables and Jeremy Smith

Matt Venables took a break from prepping Van Helsing season 4 last week to join the Scripted Series Lab for lunch. We were very eager to ply him with questions, as well as mac and cheese!

You work as part of a writing team with Jeremy Smith. What are the pros and cons of working as a team?

The cons? You split the money. We’re not greedy guys so it’s not really a con for us. The pros? It’s a mini writers’ room! We’ve always got each other to bounce ideas off with. We’re always pushing each other, building off each other. Being in a team taught us a lot about being in a writers’ room before we were really in a room because we learned not to be precious about everything we write. Be passionate, but not precious.

How do you and Jeremy complement each other as writers?

We joke that I build the foundation and then he finishes the house. I put in a lot of the structure. He almost always does the final pass. Apple TV changed the way we wrote because now we can put a script on a screen now and go through it together, screen by screen, line by line. If there’s something one of us wants to change, we highlight it.

How do you get your voices to match throughout a script?

Again, Apple TV! We go through the script together. Also, the final pass, which is usually Jeremy, ensures that voice issues get smoothed out. He sends it to me after the final pass, and if there’s something I want to adjust, we can do that. We don’t like to use email for this because that can get in the way of the communication.

What are some of the struggles you two have had together with ego?

We haven’t really had ego issues. Sometimes one of us will be really into an idea and the other person just isn’t feeling it. I pitched Jeremy an idea for a comedy and he didn’t want to do it. I think I wasn’t doing a good job of explaining it. I finally just wrote a draft so he could read it, and then he was like, “oh yeah!” and he got into it.

How do you guys sort out doing a pitch?

I’ll start with the back story of why the project is important to us, then he’ll take the lead from there. Jeremy likes to talk more than I do. I’ll interject once and a while.

Do you have any advice for those first early days in a writers’ room?

If you can get in as a writer, awesome, do it. I’m big on doing script coordinating first though. I think it teaches you a lot about the job, and what it takes to be a story editor and the whole script process for production. It’s a lot of work. If you don’t know what a script coordinator does and you’re a story editor, you’re probably leaning on the coordinator too much. It’s invaluable to have done that job.

Also, I would say be persistent. It’s a long road. For us, it took twelve to fifteen years. Rooms in Vancouver were so rare, and we were also finding our voice. We were lucky, and we were prepared when we got the opportunity.

Everything you learn, in any position, that helps you understand how the machine works, is going to be useful. We both worked as office PA’s. I’ve worked as a locations PA, I’ve collected garbage on set…to me it’s all relevant knowledge. You’re better for it in the long run if you know how the machine works because you can catch problems before they fall through the cracks. As a showrunner, that’s invaluable. The little things add up, so fix everything in prep. For that, you need to know how it all works.

What’s Your Advice for Getting yourself on the list of script coordinators who get an interview?

Ink drinks is a good place to meet other writers. It’s a great community. Get a job in the industry however you can, then start making those connections. I got my first opportunity as a script coordinator because a producer I had worked for, (as a Producer’s Assistant,) knew I wanted to be a writer. She gave me the heads up about a room that would be starting up, and that got me an interview.

It’s about putting yourself out there and making connections.

Now that you and Jeremy are developing more of your own stuff, what’s your process for developing new material?

It’s pretty much the same as in any writers’ room. We do a lot of talking, and we have corkboards in our houses. We card everything.

What’s your advice for creating good pitch material?

I would google “successful pitch document.” Try to show the tone of the show. Have a firm understanding of your characters. Be concise in what your story is. It’s hard, so be passionate about your material! Also, you’re selling yourself as much as you’re selling the project.

Q&A With TV Writer Gemma Holdway

This week our Scripted Series Lab participants welcomed writer, Gemma Holdway, to one of our “order lunch and then ask so many questions that she has no time to eat,” sessions. Gemma’s credits include consulting producer on The Murders, story editor on Ghost Wars, and Cardinal, as well as script coordinator on Gracepoint, and High Moon.

How did you make the transition from film school to being a working writer?

I started writing TV movies on spec and meeting with MOW (Movie of the Week) producers, and had some success with that. Generally, they don’t care if you have credits. They just want a script.

At the same time, I was trying to get into scripted TV. I got my first job on an American show, High Moon, as a producers’ assistant, clearances coordinator, and script coordinator. It was a lot to take on, but I made some good connections doing that job. I had to learn how to script coordinate on the fly, but it led to other script coordinating gigs. While doing that, I always made sure that people knew I was a writer, and that I had samples.

I find that when you do script coordinating again and again, people want you to stay in that role because you’ve proven yourself as an asset in that capacity. Eventually, I found I had to speak up and ask for a story editor credit as well. So, on Ghost Wars I was script coordinating but I was also a story editor. I pitched ideas but I was also taking notes, preparing script for production and I wrote an outline on that show, so I got a “story by” credit.

After that experience, I decided not to take any more script coordinating work and was able to transition to just being a writer.

I’ve heard some people say, in Canada, they expect people to do three full seasons of script coordinating before they’ll consider moving you up. I script coordinated on full seasons, pilots, MOWs and features. But script coordinating for features or TV movies won’t advance your TV writing career.

What was the transition to going in as a story editor like for you?

For a long time, as a script coordinator, I had to read the room. Some people don’t want you to participate much at all and others do. Even in rooms that were less open to my participation, I would keep pitching to some degree, but cautiously.

In some larger rooms, you may get the message from the top that everyone can participate, the best idea wins but you might get sideways looks from mid-level or junior writers. I had to decide, “Am I going to please everyone at the table, or am I going to focus on pleasing the showrunner?” That can be a constant struggle. I do think you need to be mindful of the hierarchy in the room. Give space to the senior writers, try not to interrupt, and find the right moments when it’s safe and a good idea to pitch.

When I moved into being purely a story editor, the next challenge was stepping up to the plate. There are different pressures on you. I’m naturally a bit shy, so I was nervous about putting myself out there. With help from showrunners like Damon Vignale, I learned I had to just pitch every idea. Sometimes it was really embarrassing, but in the long run, it’s worth it even if you’re going to make a fool of yourself. You’re paid to come in and pitch those ideas. A lot of people want that job, so you need to prove your worth. It’s scary but it can also be a lot of fun.

Larger rooms can be very political. You might have a few people doing most of the talking, but you can often expand on/add to someone’s pitch. You don’t want to just tear other people’s ideas down unless you have a good alternative.

How many spec samples did you have when you went looking for an agent?

I think my agent was willing to invest in me because of my script coordinating experience. Often that’s a good way into a story editing job.

I had four pilots. My interests are broad, so they were all across the board, genre-wise, all one-hour dramas though. Now I also have a half-hour dramedy that I wrote last year.

When you get an agent, you still need to hustle. You can’t just rely on the agent to get you work. They’re submitting your work, setting up meetings for you and negotiating your contracts but I also set up meetings for myself.

What’s the usual ladder of seniority in a room?

You start as maybe a writers’ assistant and/or script coordinator. Then you’re a story editor, then an executive story editor.

Often, it’s useful to look at producer credits to understand the hierarchy in the room. Going up the ladder there might be a consulting producer, co-producer, producer, supervising producer. It gets confusing, but those are middle of the pack.

The “second” in the room is often a co-executive producer. Your showrunner is an executive producer.

How, when and where do you like to do your writing?

That’s a good question. I have a red couch and I like to sit there and write, but if I’m on a tight deadline, I’ll move around a lot. I use the Pomodoro Technique, where I write for twenty-five minutes, and then take a break, and then write again.

Do you write chronologically?

I do, but I need to stop doing that! You should write the scene that you’re most excited to write in that moment.

Can You Spot the Screenwriters?

Mike Orlando is a convert to the time-tested index card method of breaking a show. “It looks like chaos, but it’s actually really handy,” he says. “It’s especially useful when you find yourself changing something in one episode, and then you have to sort through and adjust scenes in other episodes.”

Scott Meyers, @GoIntoTheStory, has a good description of the index card method here, on the official screenwriting blog of The Blacklist.

What other screenwriting wisdom is being shared? Now that we are well and truly into the swing of the Scripted Series Lab, I asked Petie Chalifoux and Mike Holland how the reality of the program differed from their expectations.

Petie says she came from a short film and feature writing background. Knowing how little she knew about the world of TV writing, she says she arrived with a very open mind and few expectations. After several weeks of story room immersion, Petie is happy to report that she has much more perspective, and a better knowledge of this side of our industry.

Mike is impressed by the intense pace and workload required of participants. As he puts it, “It’s a good thing this is what I love to do.”

Lunch with Van Helsing writer and producer, Jeremy Smith

TV Writer and Producer, Jeremy Smith, joined us for lunch last week, despite being in the thick of prepping for Van Helsing season 4. We were all impressed with Jeremy’s productivity and the volume of work he manages to juggle so successfully. Jeremy’s advice for aspiring TV writers is to be a positive person in the room, and to foster those business relationships. As he puts it, “It’s not just how good you are at creating story. Relationships are a big part of it.” You need to be someone people want to be in the same room with for months at a time.

Thank you, Jeremy!